Forests Monitor

Exploring sustainability challenges in national forest inventories: Tunisia and Mongolia as case studies

Exploring sustainability challenges in national forest inventories: Tunisia and Mongolia as case studies

Pia Knostmann, a* Till Neeff, b Max Krott, a Christoph Kleinn c

a: Chair of Forest and Nature Conservation Policy and Forest History, Georg-August-University,

Göttingen, Germany.

b: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla,

00153 Roma, Italy.

c: Chair of Forest Inventory and Remote Sensing Georg-August-University, Göttingen, Germany. *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]

Citation: Knostmann P, Neeff T, Krott M, Kleinn C. 2025. Exploring sustainability challenges in national forest inventories: Tunisia and Mongolia as case studies For. Monit. 2(1): 1-48. https://doi.org/10.62320/fm.v2i1.16

Received: 11 November 2024 / Accepted: 3 February 2025 / Published: 25 February 2025

Copyright: © 2025 by the authors

ABSTRACT

National forest monitoring provides data to inform policy- and decision-makers about a country’s forests, assessing forest characteristics and its changes. Global South countries receive financial and technical support from international donors and bilateral aid agencies for National Forest Inventory (NFI) projects as key components of National Forest Monitoring Systems. Repeating NFI is necessary to assess changes in forest characteristics and inform decision-makers; however, the vast majority of developing countries do not repeat NFIs independently of foreign assistance. While drawing attention to the term ‘Country Ownership’, this article seeks answers to the question of how interests and power of collaborating actors from Global North and South impact the implementation of NFI projects and their repeatability. The article is based on a qualitative empirical approach with theoretical entries from Weberian power theories and international relations. We conducted a study of two internationally assisted NFI projects in two developing countries, Mongolia and Tunisia. Aligned with three stated hypotheses, our empirical findings from the two cases show 1- interests of Global North actors shape NFI projects from early implementation phases; 2- a lack of consideration, especially of informal interests of national actors, builds obstacles to the implementation of NFI and their repetition. Additionally, we argue that non-state actors should become more central to NFI projects as well as in the concept of ‘Country Ownership’ in the context of forest monitoring because their participation bears the potential to create momentum for NFI-repetition, in other words, their sustainability.

Keywords: actor centred power, aid agencies, country ownership, forest monitoring, global South, national forest inventory

INTRODUCTION: CHALLENGES IN REPEATING NATIONAL FOREST INVENTORIES (NFI)

Forest monitoring belongs to a set of technical solutions sought by country governments and the international community to respond to sustainability issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss and deforestation. From a technical perspective, there is consensus that making informed decisions about forests at national and global scales demands data on forest characteristics and their changes (Corona et al. 2003; FAO 2020; Neeff and Piazza 2020). National Forest Inventories (NFI), commonly also employing remotely sensed data, are the backbone of forest monitoring. They generate the demanded scientific data and, if conducted repeatedly, their change. NFIs are based on statistical principles and generate estimates of forest variables at a defined point in time from all available data sources, which include field sample plots, remotely sensed data and statistical models (Vidal et al. 2016; AWF 2020).

There are multiple examples of how NFI data can inform political decision-making across regions, support problem recognition and the process of finding solutions (FAO 2020b). Repeating NFIs, however, is a long-term program demanding technical and financial inputs over longer time periods. Not exclusively, but especially countries of the Global South[1] rarely meet the objective of periodically repeating NFIs (Nesha et al. 2022) after receiving foreign assistance to conduct it.

Internationally assisted NFI projects have taken place in many developing countries. Besides accomplishing a nation-wide inventory of the forests, these international projects aim at enabling continuous nation-wide forest monitoring, often by setting up National Forest Monitoring Systems (NFMS)[2]. In the ideal scenario, a mandated governing body oversees forest monitoring by planning and executing NFIs periodically and evaluating the results over time (FAO 2017, p.1) while maintaining the accumulated institutional knowledge.

However, the idea of repeating similar NFI over a longer period is rare in practice. Holmgren and Persson (2003) stated that of 137 Global South or developing countries, only 22 had repeated inventories. Roughly two decades later, Nesha et al. (2022) found that 94% of the countries that relied on a single NFI are located in the Global South. A related study of 38 developing countries focusing on forest monitoring pointed to a failure rate of 75% of long-term maintenance of forest monitoring systems, stating that out of four countries, only one maintained forest monitoring for a decade or more (Neeff and Piazza 2020). Tewari and Kleinn (2015) studied the successful case of repeated NFIs in India. The authors explain the lack of repeatability of NFI in other developing countries with insufficiencies regarding technical capacity, institutional setting, and funding (ibid.).

The literature on NFI, hence, underlines that the sustainability (in the sense of repeatability and long-term impact) of forest monitoring and NFI is at risk, especially in the Global South. Yet, the publications mainly focus on policy recommendations for NFI implementation and institutionalisation (Holmgren and Persson 2003; Tewari and Kleinn 2015; Kleinn 2017; Neeff and Piazza 2020; Henry et al. 2021). Articles that touch on the lack of NFI sustainability are based on practitioners' experience or numeric studies.

NFIs do not only inform policy processes with forest data. Since national and international policies (e.g. UNFCCC (2011) demand repeated NFI, conducting NFI is, in fact, a question of policy implementation itself. Policy implementation means the factual realisation of political policies in practice (Knill and Tosun 2015; Grunow 2017).

Repeated NFI in developing countries that receive financial and technical inputs from foreign donors and aid agencies are a special case of policy implementation because they combine components of integrating science into practice, collaboration between the Global North and South, and data production.

Crucial factors that determine the implementation of policies are the interests of actors involved and impacted by the policy in question and the power dynamics between these actors (Krott 2005; Krott et al. 2014; Schusser et al. 2016; Pamme and Grunow 2017; Nago 2021; Symphorien Ongolo and Krott 2023). The impact of actors’ interests and power on policy implementation, is confirmed also for policies that aim at integration of science into practice (Böcher and Krott 2016; Krott and Zavodja 2023), policies and projects of collaboration between the Global North and South (Ongolo and Karsenty 2015; Rahman and Giessen 2017; Burns et al. 2017; Nago and Krott 2020) and policies regarding data production and transparency (Janz and Persson 2002; FAO 2020b; Brockhaus et al. 2024).

Analysing policy implementation is a subject of political science (Knill and Tosun 2015), which use qualitative empirical methods to analyse actor’s interests and power (Maryudi and Fisher 2020; Zhao et al. 2022). However, the case of the long-term implementation of NFIs in developing countries has so far not been critically analysed using qualitative empirical methods. In fact, the authors know of no qualitative study that, in the context of NFI, focuses on actors' interests and power dynamics between assistance providers in NFI projects and actors of the recipient country. Thus, to elucidate the causes of lacking repeatability of NFIs in the Global South, we ask, how informal and formal interests and applied power elements of the collaborating actors impact the implementation and repeatability of NFIs in the Global South.

To answer this question and to contribute knowledge to the identified research gap, we conducted two qualitative empirical case studies of NFI projects that aimed at the establishment of long-term forest monitoring, one in Mongolia and one in Tunisia. Both projects were realised with the financial contribution of foreign donors and the assistance of aid organisations. To analyse the power dynamics between these actors of international collaboration on NFI, we selected the actor-centred power (ACP) approach (Krott et al. 2014). The ACP builds on Weberian power theories and draws close attention to the inquired variables “interest” and “power”. The ACP framework differentiates power into three elements: dominant information, (dis)incentive, and coercion, which actors use to pursue their interests (ibid.). The power elements ‘incentives’ and ‘dominant information’ are acknowledged to crucially shape the relationship of actors representing the Global North and South, especially in the context of international collaboration on climate and forest issues (Karsenty and Ongolo 2012; Giessen et al. 2016; Rahman et al. 2016; Burns et al. 2017; Nago and Ongolo 2021). Further, the ACP approach distinguishes actor’s formal interests and informal (“hidden” or “vested”) interests, which are of particular relevance in the context of forest policies and forest data (Janz and Persson 2002; Rahman and Giessen 2017; Maryudi and Fisher 2020; Zhao et al. 2022). Based on this framework, we analysed the involved actors' interests, mobilized power resources, and their impact on the implementation of the NFI projects and NFI´s repeatability.

Due to the component of international collaboration in this specific setting of policy implementation, another way to analyse the issue of NFI repeatability could have been to assess the extent of Country Ownership as of the four categories described by Buiter (2010). Thus, because of the ownership term's ambiguity, we refrained from focusing on this approach. However, as the ownership term is used by practitioners in the context of NFI implementation in developing countries and Aid Effectiveness in general, we critically consider it in section two of this article and our conclusion.

Another eligible framework for analysing the policy process around NFI implementation was the Governance Analytical Framework (Hufty 2011). We favoured the ACP, however, because of its focus on actors' interests and analysis of power in the interaction between actors. As argued above, the theoretical entries “interests” and “power” have a high potential to explain issues of policy implementation in the context of North-South collaboration on forest monitoring.

GLOBAL DEMAND ON FOREST DATA AND THE LACK OF REPEATED NFIs in DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Demand for forest data from an international perspective

While country governments use forest data to inform national decision-making and policy processes (FAO 2020; Kleinn et al. 2020; Neeff and Piazza 2020; Tewari et al. 2020), there is a growing demand for forest data from the international side (Kleinn 2017). In this vein, developing nations receive Official Development Aid (ODA) and international technical assistance (Saket et al. 2010). Historically, the provision of foreign aid and technical assistance from the Global North agencies for executing NFIs started in the 1960s (Holmgren and Persson 2003; Garzuglia 2018, compare Box 1). Since the 1990s, the flows of financial foreign aid for forest inventories have been increasingly boosted by the demand for forest data from multiple international agreements[3] and the Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) mechanism, which was introduced in 2008 (compare Figure I Appendix).

Numerous aid agencies provide developing countries with technical and financial assistance for conducting NFI projects to deliver the required data. These actors include multilateral and bilateral development agencies and donors (JICA 2017, KLD 2021, Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft 2023, Ramírez Zea 2019, EU 2023).

On the recipient side, a growing list of countries have already received assistance for NFIs. Before 2015, over 45 countries have received assistance to set up NFIs (Tewari and Kleinn 2015). About 70 countries have submitted REDD+ reference levels to the Convention (UN 2024) and consequently need a forest monitoring system consisting of NFI and greenhouse gas inventories to receive financial compensation from the REDD+ mechanism (UNFCCC 2023).

NFI project cost and flows of Official Development Aid (ODA)

Linked to the international policy level, a variety of members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), representing the Global North, act as multilateral and bilateral donors and finance NFI projects in developing countries (Allan and Dauvergne 2013). Bilateral donors are ministries of Northeast Asian, European and North American countries. Multilateral donors include development banks, for example the World Bank.

ODA which is utilized for NFI projects in recipient countries of the Global South, falls under the OECD sector “forestry” (OECD 2024a). Of bilateral commitments, ODA flows to this sector were at an annual average of 1.5 billion USD between 2018 and 2022 (OECD 2024b). NFIs are often part of larger forestry projects, making estimating the exact ODA volume used for NFI difficult. However, before the REDD+ mechanism was introduced, FAO reported costs of NFI projects between 0.5 and 4 million USD per country (FAO 2008; 2020)[4].

As examples of REDD+ related inventory projects, the cases studied in this article cost EUR 3.1 million (corresponding to USD 2.8 million in 2016) in Mongolia (MMET 2016) and USD 6.3 million in Tunisia (FAO 2025)[5]. In 2020, the officially reported forest cover was 14,173,000 ha for Mongolia and 703,000 ha for Tunisia (FAO 2020a), corresponding to 9.1 % and 4.3 % of each country’s respective total land area[6]. Given that neither of the countries is a top-forest cover country, it is noteworthy that NFI cost depends on personnel hires, defined NFI indicators, sampling methods and density, and infrastructure.

Both internationally assisted NFI projects aimed at 1- producing forest data based on NFI for national and international use, 2- setting up a frame that allows repeat the inventories periodically, and 3- disseminating the collected data transparently to the international level responding to data requirements of the REDD+ mechanism and the FAO Forest Resource Assessment (FRA).

Country Ownership’ of NFI projects

In discussions of Aid Effectiveness, leading development organisations refer to the term ‘Country Ownership’ or ‘National Ownership’ as the alleged country´s responsibility for project formulation and implementation (OECD n.d.). The term was first introduced by the World Bank in 1996 (World Bank 1999). In 2005, ownership became the first principle of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Here, ‘Ownership’ is defined as agenda setting in national development strategies.

“1. Ownership. Developing countries set their own development strategies, improve their institutions and tackle corruption.” (OECD n.d.)

Introducing the ‘Ownership’ term aimed at changing the development paradigm from conditional aid to the support of domestically set development agendas.

In NFI projects in developing countries, the aim to repeat the NFIs periodically (usually expressed in project proposals) is not implemented. As was mentioned above, the majority of developing countries relied on single NFIs after receiving assistance (Holmgren and Persson 2003; Nesha et al. 2022). Neeff and Piazza (2020) state that approximately 66% of developing countries in their sample neither allocate continuous funding for their NFI nor employ permanent staff responsible for this task.

Four major points can be found in the literature as factors that help ensure that governments repeat NFIs for forest monitoring (Figure 1). First, 1- a continuous, internal need of NFI data for political decision makers is required (Ferretti and Fischer 2013; FAO 2020b). Further, elements that the “FAO Voluntary Guidelines on National Forest Monitoring” comprise under the umbrella of ‘National/ Country Ownership’ are expected to ensure continuous NFIs. These are 2- existing capacity/expertise of staff, 3- institutionalisation as a permanent forest monitoring department, and 4- NFI demanded on a legal basis, which allows allocation of government budget (Tewari and Kleinn 2015; FAO 2017).

Figure 1. Factors linked to ‘Country Ownership’ that are expected to guarantee continuous NFIs in developing countries after receiving foreign assistance, based on literature (Tewari and Kleinn 2015; FA O 2017; Ferretti and Fischer 2013; FAO 2020).

Whether the introduction of the ownership term, as stated above, led to a shift from conditional aid to agenda setting by recipient countries is contested by numerous political science researchers (Buiter 2010; Booth 2012; Haque and Ahmed 2012; Keijzer and Black 2020; Hasselskog 2022).

The encountered lack of repeatability of NFIs after receiving foreign aid is an issue of policy implementation. As in many cases of environmental policy implementation, existing literature overlooks the role of actors’ interests and power as crucial enablers and obstacles. The question is not only whether the recipient country delivers the required factors, as summarized in Figure 1. From a political science perspective, the context of aid flows and international frameworks demanding NFI data inevitably raises questions of ‘Country Ownership’ from a more critical point of view: Who gives the impulse for NFI projects, developing countries or foreign donors and international organisations? How are domestic and foreign interests considered in the implementation process? Who benefits from project implementation and NFI outputs? Are the technical, financial and administrative aspects of forest monitoring suitable and realistic for the recipient country?

In the final section of this article, we link the findings from our case studies in Mongolia and Tunisia to existing literature on the ownership concept. We then draw attention to aspects of the ownership term which, to our knowledge, were not sufficiently addressed in the existing technical literature on NFI and National Forest Monitoring Systems.

THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Analysing interests and power of the Global North and South actors in NFI projects

As a basis for evaluating obstacles to policy implementation, Ongolo and Krott (2023) recommend analysing the involved actors’ formal and informal interests and their power-relationship. To do so, the present research combines concepts of international relations and power theories and applies them to the context of internationally financed and assisted NFI projects in the global South. We chose the actor-centred power (ACP) approach (Krott et al. 2014) as framework because it considers clearly interests and power of involved actors, two aspects that are crucial to policy implementation and often overlooked. The ACP is based on Weberian power theory, understanding power as actors’ aim to execute their own will for satisfying their interest from a resource regardless of interests and resistance of other actors (Weber 2002 in ibid.).

An actor is defined as a person or organisation that can influence a policy and policy implementation (Krott et al. 2014; Schusser et al. 2016). Actors’ interests are defined as direction of action to obtain benefits from a resource (Krott et al. 2014). In the studied cases, resources from which actors aim to derive benefits are forests and public financial resources, especially ODA. We differentiate between formal interests, which are visibly displayed in project literature, official mandates and websites; and informal interests, such as maximising self-benefits, which actors intend to conceal (Schusser et al. 2015; S. M. Rahman and Giessen 2017; Zhao et al. 2022).

In the context of National Forest Inventory (NFI) projects, we understand funding organisations and aid agencies, including those providing assistance, as Global North actors who aim to promote forest monitoring in the Global South based on formal interests or goals such as international agreements (Box 1, Figure I appendix).

|

Box 1: History of NFIs and foreign interventions promoting forest monitoring in the Global South Since the early 20th century, national forest inventories have become increasingly complex and evolved from inventories focussing on timber supply to multipurpose inventories (Branthomme 2010; Kleinn 2017). “Multipurpose” refers to the multiple objectives that forest inventories have nowadays (FAO 2024b). The purposes depend on stakeholders and may include biodiversity and health, carbon sequestration, and socioeconomic aspects, while also considering the needs of populations living close to forested areas. Statistical sampling was introduced into scientific methodology at the end of the 19th century as “the representative method” (Kruskal and Mosteller 1980). Today, forest inventories are based on statistical sampling by default. The first of such statistical NFIs have been carried out in the forests of Scandinavian countries, starting with Norway (1919-1930), followed by Finland (1921-1924) and Sweden (1923-1929) (Kleinn et al. 2020). These inventories focused on timber supply and were widely adopted across the Global North. The focus on timber production also applies to the 1860s’ teak inventory in today’s Myanmar (Hesmer, 1975 in Kleinn et al. 2020), which aimed at wood extraction for the British crown (Bryant 1996). After the Second World War, frameworks demanding global forest data emerged hand in hand with foreign assistance for the establishment of NFI in developing countries. Due to a high wood demand linked to post-war reconstructions, UN-FAO was mandated from 1948 onwards to assess the world‘s forest resources and started conducting the Global Forest Resource Assessments (FRA) in ten years periods, which was shortened to five years from 2000 onwards (Garzuglia 2018). In this vein, international assistance was provided to developing countries to set up their NFI from the 1960s onwards (Holmgren and Persson 2003). The majority of recipient countries did not continue monitoring their forests after such interventions (FAO 2008), with India as one of the few exceptions (Tewari and Kleinn 2015). Starting in the 1970s, remote sensing (forest assessment via satellite images) emerged as an additional data source in monitoring, which previously had been restricted to field samples (Holmgren and Persson 2003). This led to the combined system of field inventories and integrated remote sensing data as endorsed today (FAO 2017). Since the 1990s, themes from the international policy level, such as forest biodiversity, carbon sequestration and socio-economic relevance of forests, have been added to the purposes of NFI and forest monitoring systems (Corona et al. 2003). Consequently, the set of variables recorded to characterize the forests on the national level increased. The new information and data needs emerged largely from international conventions, including the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, the UN-FCCC, and the 2030 UN-SDGs, notably forest indicators as forest area and sustainable forest management (Ferretti and Fischer 2013; FAO 2024c). With the incentive of result-based payments in case of reduction of deforestation and forest degradation, the UN-FCCC’s REDD+ mechanism has demanded that developing countries set up national forest monitoring systems since approximately 2011 (UNFCCC 2011). |

Simultaneously, we consider informal interests of donor and recipient organisations as drivers of action, since development research analysing forestry projects in the Global South highlights the importance of informal Global North interests for policy implementation (Andreas 1999; Ongolo and Karsenty 2015; Rahman and Giessen 2017; Nago and Krott 2020; Maryudi and Fisher 2020). These conceptual entries lead us to the first hypothesis H1.

H1: Actors of the Global North formulate and implement forest inventory projects in the Global South based on their informal and formal interests.

Following the concept of Zhao et al. (2022), the detection of formal interests can be achieved by revising policy documents, whereas informal interests can be identified via observation of actions and non-actions.

The ACP sees relationships of actors as a struggle for the benefit of resources. In this struggle, actors seek to dominate other actors (Krott et al. 2014), via three types of power elements that actors use to influence other actors, namely:

- dominant information,

- incentive and disincentive,

- coercion.

Ongolo and Krott (2023, p.252) list three strategies employed by weaker actors to resist domination. These resistance strategies are respective to the power resources:

- opposition, withdrawal,

- tardiness, cheating, boycott,

- inertia (ibid.).

Forest monitoring is a highly technical discipline anchored in natural science. In the Global North, where national forest monitoring is widely established, the role of natural science has historically evolved as a tool supporting political decision-making of institutions (Krott and Zavodja 2023, p. 49). Informed decision-making based on natural science is also in line with the formal goals of forest administrations of the Global South. However, developing countries’ institutions are often characterised by instability and insufficient funding (Buiter 2010; Karsenty and Ongolo 2012; Reeves 2014; Hasnaoui and Krott 2019; Aloui et al. 2021). Here, the uptake of scientific information requires a match with informal interests (including power expansion and acquirement of revenues) of the actors that access the scientific information (Krott and Zavodja 2023). In other words, the integration of scientific knowledge must exceed formal goals such as informed decision-making on forests and bring tangible benefits for the actors in charge.

Early stages of donor projects correspond to such informal interests of domestic actors seeking ways to benefit from the intervention (Ongolo and Karsenty 2015; Rahman and Giessen 2017; Nago and Krott 2020). However, the implementation requires high efforts that can, in the long run, exceed the potential benefits that domestic actors would gain from contributing to the project. Further, in case of pronounced forest issues, counter-interest against data transparency might emerge to avoid criticism, conceal failures, and maintain the status quo of management practices and related revenues (Janz and Persson 2002). Corresponding to the abovementioned strategies of resistance of dominated actors (Ongolo and Krott 2023), we formulate the second hypothesis:

H2: Lack of consideration of domestic actors’ key interests leads to the withdrawal of domestic actors from NFIs and follow-up projects formulated and implemented by the Global North actors.

As stated above, there are numerous potential donors interested in supporting forest inventories in developing countries because it matches their formal agenda to address sustainability issues such as climate change and deforestation. As the non-repeatability of NFIs in the Global South was noted by multiple authors (Holmgren and Persson 2003; Tewari and Kleinn 2015; Neeff and Piazza 2020; Nesha et al. 2022) we expect developing countries to remain inactive after intervention and not repeat the same NFI. In this situation, the variety of foreign actors as potential donors for new forestry programmes and forest inventory projects gains relevance.

We build our third hypothesis on the observation of Olivié and Pérez (2016) that foreign donors refrain from coordinating their aid because they follow their own foreign policy objectives. In the same vein, we consider Aurenhammer's (2012) concept of foreign policy subsystems that emphasises that development agencies are mandated to implement policies on behalf of foreign donors, hence prioritising the agenda of foreign donors.

We expect that even though developing countries did not repeat previous NFIs implemented with foreign aid, new donors and implementing agencies will seek to promote forestry and NFI projects in the same recipient country. Regarding the previous donor and provider of assistance, we expect that they do not focus on long-term implementation but move on to other projects, likely in other countries. We hence hypothesize the following:

H3: Not repeating NFI does not produce losers among the engaged actors of the Global North and South, since new projects financed by the Global North compensate potential losses in a particular country.

METHODOLOGICAL ACCOUNTS

To assess the interests and power relationships of international and domestic actors collaborating on NFI projects, the present research uses a qualitative empirical approach (Maryudi and Fisher 2020; Zhao et al. 2022). In this vein, we selected two developing countries that received funding from foreign donors to conduct NFIs along with technical assistance provided by aid agencies.

Case selection

During the first round of desk research and interviews, we received many hints from country cases of internationally assisted NFI projects facing obstacles in the long-term implementation, for example, from Morocco, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Kyrgyzstan. Since the lack of NFI repeatability is a global problem, it was desirable to choose cases from different regions across the Global South as well as different donor and implementing organisations to find answers that exceed statements valid for only one country or region or one specific donor or assistance provider.

To maintain the conciseness and clarity of the study, we decided to focus on only two countries and selected Tunisia and Mongolia (Figure 2) because of data accessibility. The two cases meet three relevant criteria allowing insightful comparison of internationally funded projects for nationwide forest inventories: First, 1- different regions, 2- different donors and 3- different implementing agencies.

Figure 2. Map indicating the two countries selected for case studies of international projects for National Forest Inventories, Tunisia (left) and Mongolia (right).

Tunisia is a country from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region with a subtropical Mediterranean climate, whereas Mongolia is a land-logged North Asian country with a temperate continental climate and mainly boreal forests.

In Tunisia, the NFI project was financed with a World Bank loan and assistance from the UN-Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (MARHP, Republique Tunisienne, and World Bank Group 2024). In Mongolia, the inventory project was financed via a grant from the German Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and assisted by the German development agency GIZ and contracted consultants (MMET 2016).

Both countries, Tunisia and Mongolia, share a long history of foreign rule or influence, with Western influence growing after moments of political rupture. Tunisia was occupied by the Ottoman Kingdom until 1881, when it fell under the French protectorate and only reached its independence in 1956 (Levy 1957). In Tunisia, western organisations supported the development and economic growth throughout the second quarter of the 20th century but intensified interventions after the 2011 Arab revolution (Hasnaoui and Krott 2019) to support peaceful democratisation after the authoritarian rule. Mongolia was under Chinese rule until 1911 and achieved its independence in 1921, in the context of an intensified relationship with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics USSR (Ewing 1980). In the subsequent period, some authors portray Mongolia even as a USSR satellite state (Bedeski 1970; Reeves 2014; Jargalsaikhan 2018). In the 1990s, Mongolian politicians actively sought Western aid when the country shifted from a planned to a market economy (Buyandelgeriyn 2007). In that decade, western influence gained in importance, including in land-use policies (Sneath 2003).

Data collection and ethical considerations

Empirical data was collected between 2020 and 2024 from policy and project documents, key-informant interviews, and direct observations (visiting offices and laboratories). For the Tunisian case, two field visits were realised in Tunisia from April to May 2023 and in December 2023. Data regarding the Mongolian forest inventory project was collected between August 2023 and February 2024, remotely and in personal interviews with former project-related experts online and in presence in Germany.

The research aim was explained to interviewees before starting the inquiry. Confidential treatment of the data (pseudonymisation) and the strict use of the data only for academic purposes were promised. Due to the sensitivity of the data, it was pseudonymised and only actor classifications are listed in the appendix to this article, while the interviewees’ roles in the organisations are kept confidential (Table I, appendix).

A total of 36 interviews (25 for Tunisia, nine for Mongolia, and two not country-specific) were conducted between November 2020 and January 2024. Semi-structured interviews were carried out online via Zoom and phone calls and in presence during field visits. Data to clarify remaining questions was assessed via questionnaires and emails. In our inquiry, we tried to consider all actor types of involved international and domestic actors to best crosscheck the collected data. However, despite multiple trials, we did not receive an answer from the state actor in Mongolia. Therefore, we tried to complement missing information via document analysis and peer-reviewed literature.

Over 40 policy documents, press releases, project reports, internal documents and drafts were collected and viewed. These are cited throughout the results section. The data from policy documents was used to specify interview questions and triangulate collected interview data and data from observations.

Data analysis

Along with the formulated hypothesis the data analysis and results’ section are divided in three parts:

- To test the first hypothesis, we reconstructed the project history to assess the roles of the Global North and the Global South and power elements used by actors during the project formulation stage.

- The second hypothesis is tested with empirical data concerning formal and informal interests, conflicts and struggles of implementation, along with an analysis of how actor mobilized power elements (mainly ‘incentives’ and ‘dominant information’) of the analytical framework, ACP.

- To test the third hypothesis, we adopted a historical perspective comparing previous NFIs and the role of international donors in order to assess system inertia (halt) after intervention as well as losses among actors of the Global North and South.

RESULTS

Global South and North actors collaborating in National Forest Inventory projects

Across the Global South, a range of domestic and international actors collaborate to design and implement large-area forestry projects that often include NFIs. In this context, we differentiate between four actor groups:

- international donors,

- assistance providing aid agencies,

- domestic governmental organisations,

- domestic non-governmental organisations.

International donors are typically linked to industrialized countries representing the Global North. These donors can be multilateral or bilateral. In most cases, they are not present during the intervention for the NFI project but delegate the task of implementation to aid agencies that provide technical assistance. However, donors allocate the financial resources for forest development projects to achieve their formal goals of foreign policy and sustainable development.

Aid agencies can also be multilateral or bilateral. Multilateral aid agencies are, for example, UN specialized agencies such as the UN-FAO. Agencies that operate bilaterally are typically development agencies of industrial countries such as the GIZ, the German development agency. These aid agencies have their own staff and may additionally hire international and domestic consultants as advising experts for the NFI project. Often, the agencies’ responsibility exceeds merely technical tasks as they are entrusted with the design and implementation of NFI projects and the management of the budget.

On the recipient side, government bodies, such as ministries that oversee forest lands and the affiliated forest administrations, collaborate on the international policy level with foreign donors and on the operational level with the aid agencies. In many developing countries, including the two studied countries, the allocation of government budget for forest-related activities is quite limited. This is due to a general lack of funding for forests - which may be interpreted as assigning a low priority and minor interest in forest resources. This possibly results from competition with other sectors, such as infrastructure, defence, and health, that might rank higher on the government agenda (interview 10, 21). In addition to the financial contribution provided by Global North donors for the projects, the technical assistance for conducting NFI and forest monitoring is attractive not only for the government body but specifically for the staff of forest administrations as an opportunity for networking and acquiring additional skills.

The fourth actor group comprises non-state actors in the recipient countries: Academic and research organisations, private forest companies, NGOs and forest-adjacent communities. These are not only considered in the frame of the data collection but can play an active role in the implementation of NFI. Non-governmental actors can play a crucial role in regard to ‘Country Ownership’, which will be highlighted in the discussion.

The specific domestic and international actors of our case studies are listed in Table II in the appendix.

NFI context and actors from the case studies

Tunisia: The first nationwide forest inventory in Tunisia was conducted in 1995 in the frame of a forestry programme financed with a World Bank loan (DGF 1995, World Bank 1996). This inventory was based on field data collection. No field data was collected for over 25 years until the NFI project we analyse here was launched in 2019. However, in 2005, aerial images of the forest cover were collected, analysed and later published as a second forest inventory (Selmi et al. 2010). The 2005 inventory was financed by state budget (ibid.).

In 2019, the project Inventory of Forest, Pastoral and Olivetree Resources (in French, Inventaire des Ressources Forestières, Pastorales et Oléicoles IFPON) was launched. It was supposed to be completed by December 2023 but faced multiple delays and the time of completion was shifted to summer 2024 (FAO 2024d; 2024a).

The project was financed via a World Bank loan as part of a larger project, the Integrated Landscapes Management in Lagging Regions project, worth approximately USD 100 million (World Bank 2017a). According to the project appraisal, a total sum of USD 8 million was calculated for the NFI project IFPON (World Bank 2017, p.14). The aim of the IFPON project was to conduct inventories and set up a system that monitors forest, rangelands and olive tree stands (MARHP et al. 2020). The aim is to repeat inventories in a cycle of four years (interview 24).

UN-FAO was the international aid agency that assisted in the implementation. It obtained the position because of its strong expertise in forest monitoring and to support the national forest administration (interview 5). To define the target variables of the inventory, the project managers revised existing policy documents compared them to the data demands from international frameworks and consulted national experts for setting up the NFI design and technical setting for data sharing, analysis and storage (MARHP et al. 2020, p. 16, interview 16).

The main national actor for implementation is the Tunisian forest administration, Direction Générale des Forêts (DGF), taking on tasks of coordination, for example supervising fieldwork (MAHRP et al. 2023). Other domestic actors were the regional commissariats (CRDAs) that provided a workforce for the data collection together with recruited assistants (MARHP et al. 2023) and the Tunisian Forest Research Centre, which had a role in field data collection and analysis in its laboratories (interview 20). All of the domestic actors mentioned are relatively closely related to the government.

Mongolia: The first nationwide forest inventory in Mongolia was completed in 1956 with technical assistance from Russian forest experts (FAO 2007, p. 6). No nationwide inventory was realized until the Mongolian Multipurpose National Forest Inventory (MPNFI). It was conducted from 2012 to 2016 and grant-financed by the German Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) (MMET 2016). Hence, there was a gap of 60 years between the two inventories, and both received inputs from different foreign sources, Russia and Germany.

The overall budget for the recent NFI project was EUR 3,105,000 € (MMET 2016, p. 119). The German development agency (GIZ) was commissioned by the donor, BMZ, as an agency to assist in the implementation of the forest inventory (ibid p. 5). In addition to their staff, GIZ hired foreign consultants to set up the NFI design and train local staff in data management and analysis and field data collection (interviews 27 and 30).

The Mongolian forest administration was the most important state actor in the frame of the NFI project, with the Forest Research and Development Centre actively participated in training, analysis and dissemination activities (MMET 2016, interview 30). Further, A range of domestic non-state organisations participated in the NFI project: private consulting companies, who previously worked only for smaller-scale production forests, were trained and played a crucial role in the NFI data collection (interviews 27 and 28) and teams from four Mongolian universities for independent control measurements (MMET 2016).

Impulse and interest in NFI projects

Impulse and interests – Tunisia: For receiving the World Bank loan that financed the NFI project, Tunisia had to prove that suitable national forest policies as a basis for budget distribution were in place. The ‘National Strategy for the Development and Sustainable Management of Forests and Rangelands 2015-2024’ (SDGDFP) (DGF and GIZ 2014) was a crucial policy in this regard. This policy resulted from a project managed by international GIZ consultants and financed by the German ministry BMZ (interview 6). The goals of the SDGDFP were broken down into actionable steps with the forest investment programme led by the World Bank (World Bank, DGF, and MARHP 2016). Together, these policies contributed to Tunisia’s qualification for the loan in question (Knostmann 2021).

The SDGDFP policy aims to foster Tunisia’s qualification for the REDD+ mechanism, which is also mentioned in the project appraisal that includes plans for the forest inventory (World Bank 2023). This corresponds very well with the interest of the World Bank, which is one of the earliest and strongest supporters of the REDD+ mechanism (World Bank 2009). Further, both the NFI project and the SDGDFP policy refer to international agreements such as the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UN-CBD) and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), representing important formal interest of the international donor community.

International policies and foreign actors laid hence the groundwork for the inventory project, precisely with 1- the SDGDFP policy as the outcome of a GIZ project and 2- the following forest investment programme as the basis for the loan from the World Bank, 3- the formal focus on international frameworks and the REDD+ mechanism in policy documents, and 4- the UN-FAO as selected aid agency to implement the NFI. This reveals that the process that led to the inventory project was not solely a demand of Tunisian citizens and experts. Policies that enabled the inventory projects, were impacted by international organizations and fostered by foreign incentives (grants and loans for forestry projects).

Impulse and interests – Mongolia: In Mongolia, GIZ forestry experts gave the impulse to conduct a forest inventory (interview 27) that led to the project ‘REDD+ national forest inventory in Mongolia’ (GIZ 2017). These were already present in Mongolia (interview 27) for the project “biodiversity and adaptation to climate change of central forest ecosystems”.

During that time, the REDD+ mechanism was ranking high on the agenda of the donor, the German Ministry of Economic Collaboration and Development (BMZ) (BMZ 2015). Well responding to the donor’s interest in REDD+, the promotion of Mongolia’s participation in the REDD+ mechanism is highlighted in the official documentation of the project (GIZ 2017).

Insider knowledge from the GIZ forestry experts’ personal network on the agenda of the financing partner BMZ enabled them to tailor the project proposal according to the BMZ’s priorities (interview 27). Comparable to the Tunisian case, the agendas of the donor BMZ and the interest of the international agency GIZ shaped the early stages of the NFI project.

How in-country dynamics impact NFI projects

Barriers in moving from foreign incentives to sustained state funding for NFIs

In both NFI projects, the budget was provided by foreign donors, with the German ministry BMZ in Mongolia and the World Bank in Tunisia. For both, the aid agencies, GIZ in Mongolia and FAO in Tunisia (World Bank 2017b), managed the project budgets and hired consultants (interview 2, 5, and 25). This gave relevant power resources to the aid agencies, namely the ability to give incentives and choose the experts for NFI implementation including NFI design and capacity building.

Prior to the projects, neither the state budget nor state departments fully focussing on forest monitoring were in place. In Mongolia, forest management inventories[7] were conducted only in one province (MMET 2016). In Tunisia, a forest monitoring department existed. However, despite having some of the required technical competencies, it did not meet the capacity, concerning finance, data management and time, to fulfil the task (FAO 2019, p. 17). Nor exists a legal basis in the Tunisian forest code that mandates the department to carry out NFI and would hence justify the allocation of the state budget for this task (Republique Tunisienne 2017, interview 26).

The fact that neither of the countries had conducted recent NFIs without impulse and financial contribution from foreign organisations supports the statement that these activities do not rank high on countries’ agendas and that the ability or willingness to mobilise state budget for NFIs is low.

Most interviewed actors expressed doubt about the mobilisation of the state budget to sustain the NFIs after the international projects’ end. However, this challenge was not addressed in the frame of the projects. In both countries, capacity development focussed on technical aspects such as field measurements for the inventory, data collection, data analysis, and remote sensing (interviews 16, 22, and 30). For both cases, strategic planning and financial aspects, for example, proposal writing, fund acquisition, and accounting to conduct NFI in the future, were not included in the trainings (interviews 26, 33, 34).

In Mongolia, one source reports the promise to utilise government funding to finance the forest monitoring department‘s activities (UN-REDD Programme 2018, p. 18). Others point to a lack of capacity for forest monitoring (MMET and REDD+ Mongolia 2018a) and to delays due to the absence of the director in charge due to changes in the ministry in 2018 (UN-REDD Programme 2024). It was indicated that the department was understaffed and underfunded even during the duration of the NFI, which received funding from BMZ and assistance from GIZ, which led to considerable time constraints (interview 30).

In Tunisia, some interviewees stated that the institutionalisation of the system with a central team in charge of NFI tasks ‘only existed on paper’ (interview 22). Further, financial limitations were expected to jeopardise the periodical repetition of the NFI, pointing to a dependency on technical and financial contributions from foreign donors to continue forest monitoring.

“Support of the forest administration remains necessary. There is state-budget for the national program, which assures the system’s management. But it is not enough to ensure the updates of the system, its upgrade etc. Financial support from donors remains necessary.” (interview 24)

Even though the gap between field inventories (25 years) in Tunisia is not as large as in the Mongolian case (60 years), forest data quality and consistency are problematic. To date, all three Tunisian NFIs have used different methods, as the 1995 inventory was based on field data, the 2005 inventory on aerial images and the recent inventory on field data with a newly developed design, integrating remote sensing data. Although an inventory was planned for 2016/ 2017 (FAO 2019, p. 17) it was never carried out. Further, old data sets are not accessible as reliable sources for comparative forest monitoring. Interviewees and documents describe a lack of transparency in the database of the second inventory (FAO 2019, p. 17) and missing data/ storage problems in the data set of the first NFI (interviews 15, 22).

Putting the repetition of the latest NFI at risk, budget allocation, and technical capacity remain important issues in Tunisia. For example, multiple interviewees criticised the project duration as too short for enhancing national capacity, collecting field data (given summer months with dangerous temperature levels) and analysing it (interview 19, 20, 22). Simultaneously, financial shortcomings are expected to prevail (interview 24).

Tunisia: Political instability and other obstacles

Despite consultation with Tunisian specialists in drafting the project, national actors such as the state forest administration adopted a relatively passive role during crucial periods of the NFI implementation (interviews 13, 14, 15, 22). The first and most obvious reason for this is that the administration was weakened by political instability: Linked to multiple unsuccessful attempts to form a new Tunisian government in 2019 and 2020, frequent changes in the ministry occurred during project implementation. These changes were accompanied by the replacement of directors in charge, which built obstacles to planning and implementation (interview 2, 16). In 2023, political instability persisted. A striking example of how this affected the project implementation is that in April 2023, workshops for NFI training were interrupted due to an order from the newly appointed minister, demanding a halt of all project activities, which persisted for multiple weeks (interview 16). Political instability in developing countries is a considerable aspect influencing policy implementation.

However, we found that diverging interests are the second obstacle to NFI implementation, as project internal conflicts caused a certain withdrawal from participation. For example, conflicts arose due to the choices of supervisors and consultants that the international organisations hired despite disagreement and doubts about staff working in the domestic forest institution (interviews 1, 2, 25, 26). Prior to this, the donor-recipient relationship had already been strained by strong differences regarding a structural reform of the forest administration that the World Bank tried to promote (interviews 1 and 4).

A third reason for the reduced activity of the domestic partner were hurdles in the management of project materials. This is partly tied to actor interests, as, on one hand, delays of material delivery were caused by the Covid-19 pandemic (interviews 11 and 16). But on the other hand by high-level negotiations about payments (interview 25, MARHP, Republique Tunisienne, and World Bank Group 2024). Further, misalignments regarding the use of materials, especially vehicles (World Bank 2023) conflicted with the initial time schedule.

As a last reason that caused the domestic partner’s adaptation of a rather passive role during some stages of the project, we found the unfavourable incentive structure of the state forest administration in Tunisia. Project management activities that officially fell into the responsibility of the domestic partner were not encouraged by higher leadership since there were no additional incentives or reimbursement for the additional workload (interview 16, 25). Consequently, the activities necessary to continue the NFI project were taken over by the team that was officially contracted by the aid agency FAO who had to work towards the accomplishment of project deliverables demanded by the donor and agreed upon in the project appraisal.

The formal goal of all actors engaged in an NFI project is to make data accessible to inform decision makers and the general public about the state of the country’s forests. Accessibility and distribution of data and results can improve the momentum of NFI results to impact change. Nevertheless, the passive and even inactive behaviour of the government bodies in Tunisia built an important obstacle to reach this formal goal of distributing forest inventory information. Tasks that are restricted to government organisations, such as advertising the project´s advance and data distribution platforms to relevant stakeholders and the public via press, social media, etc., were not realised.

“The data collection platform and a framework for collecting it are in place. To my mind it is time to advertise the project’s advances and inform stakeholders and the public so that the inventory results will be expected, used and have an impact. But up to now, the ministry has done nothing to make this information known.” (interview 22)

The statement was expressed one and a half years prior to the project’s official end. In fact, the online forum, which was initially planned to overcome issues of data consistency, accessibility and transparency, was neither made publicly available nor finalized (MARHP, Republique Tunisienne, and World Bank Group 2024). This is expected to affect the durability of the NFI project’s results (ibid.).

Mongolia: Counter-interests to forest data use

Forest politics, forest management, and wood trade in Mongolia are characterised by complex and partly contradictory issues. Mongolia has 9.1 million hectares of forests, which are concentrated in the North of the country (MMET 2016). The forest area is jeopardized due to wildfires, pests, and illegal logging (Ing 1999; Gradel et al. 2019; Battuvshin et al. 2022). Simultaneously, climate change, especially extended droughts reduce resilience of trees and regeneration (Gradel et al. 2019). Because of such environmental concerns, policies restrict logging activities: harvesting of standing trees is only allowed to private companies and on only 370 000 hectares of the total forest area (MMET 2016). The species Siberian pine is entirely excluded from logging (Battuvshin et al. 2022).

As community forest management structures, households can build forest user groups (FUGs). In total, 1.5 million hectares of forests are designated for FUGs (MMET 2016). However, the activities of FUGs cannot be considered factual forest management as they are only allowed to use dead wood (MMET 2016; Battuvshin et al. 2022). Further, insufficient training (Gradel et al. 2019; Glauner and Dugarjav 2021) poses important hindrances to effective silviculture in practice. While there is a considerable need for construction and energy wood, in some sub-regions, dead wood material is accumulated (Battuvshin et al. 2022). It is even estimated that this dead wood could satisfy the national demand for several decades (ibid.). Deadwood biomass in the forest enhances the risk of pest calamities and forest fires. Paradoxically, the current development of the wood value chain leaves opportunities for economic development unused (Glauner and Dugarjav 2021). Nevertheless, such development would be much needed since the lack of economic opportunities pushes the local population to seek marketable non-wood forest products in the forests, such as pine seeds and antlers (Ing 1999; MMET 2016). The resulting enhanced presence of humans in the forests increases the risk of fires. In fact, over 95 % of fires are human-induced (Glauner and Dugarjav 2021).

While technical knowledge is available and forest policies are set up to address the issues of regeneration, fire hazard, and processing industries, there are important gaps between the formulated policies and their implementation (MMET and REDD+ Mongolia 2018b; Gradel et al. 2019; Glauner and Dugarjav 2021). In this context, it is noteworthy that key metrics for policy formulation, implementation, and monitoring remain undefined; for example, there is no exact figure of the target growing stock of forest areas, which the government must define as a basis for silvicultural concepts (Glauner and Dugarjav 2021, p.14).

Despite a considerable forest area, the Mongolian wood industry largely relies on import (MMET and REDD+ Mongolia 2018a; Glauner and Dugarjav 2021). This may create important counter-interests to how NFI data was used as we will consider below. Based on the findings of the 2016 NFI, international donor literature states that Mongolian forests are overmature and underused (AFoCO 2021) and that the annual allowable cut may be increased (MMET and REDD+ Mongolia 2018a) to harness the economic potential of this resource. However, FUGs as potential users face restrictions to harvest standing trees (MMET 2016) and although policies aimed at supporting the wood sector, they were not implemented (Glauner and Dugarjav 2021).

Seeking an explanation for these contradictions, we found that 1- there is a challenge to understand the purpose of an NFI in general[8], and 2- an overall resentment against wood utilization

“Here, cutting trees is like killing babies” (interview 30).

These are unfavourable conditions for silviculture in general, potentially limiting the diversification of the wood economy. Nevertheless, based on the 2016 inventory data, GIZ experts elaborated silvicultural guidelines for Mongolia (GIZ 2019) aiming at sustainable wood utilization in the overmature forests and enhancing the forests´ ability to store further carbon in line with the REDD+ mechanism. This also aimed at job creation and diversification of the wood processing economy with wood from Mongolian forests (ibid.).

This silvicultural concept was, however, rejected by high-ranking decision-makers. Informal counter interests linked to personal benefits from trade with imported wood (interview 27) are a possible reason for the rejection. As mentioned above, imported wood is the main source of material for the wood processing industry in Mongolia.

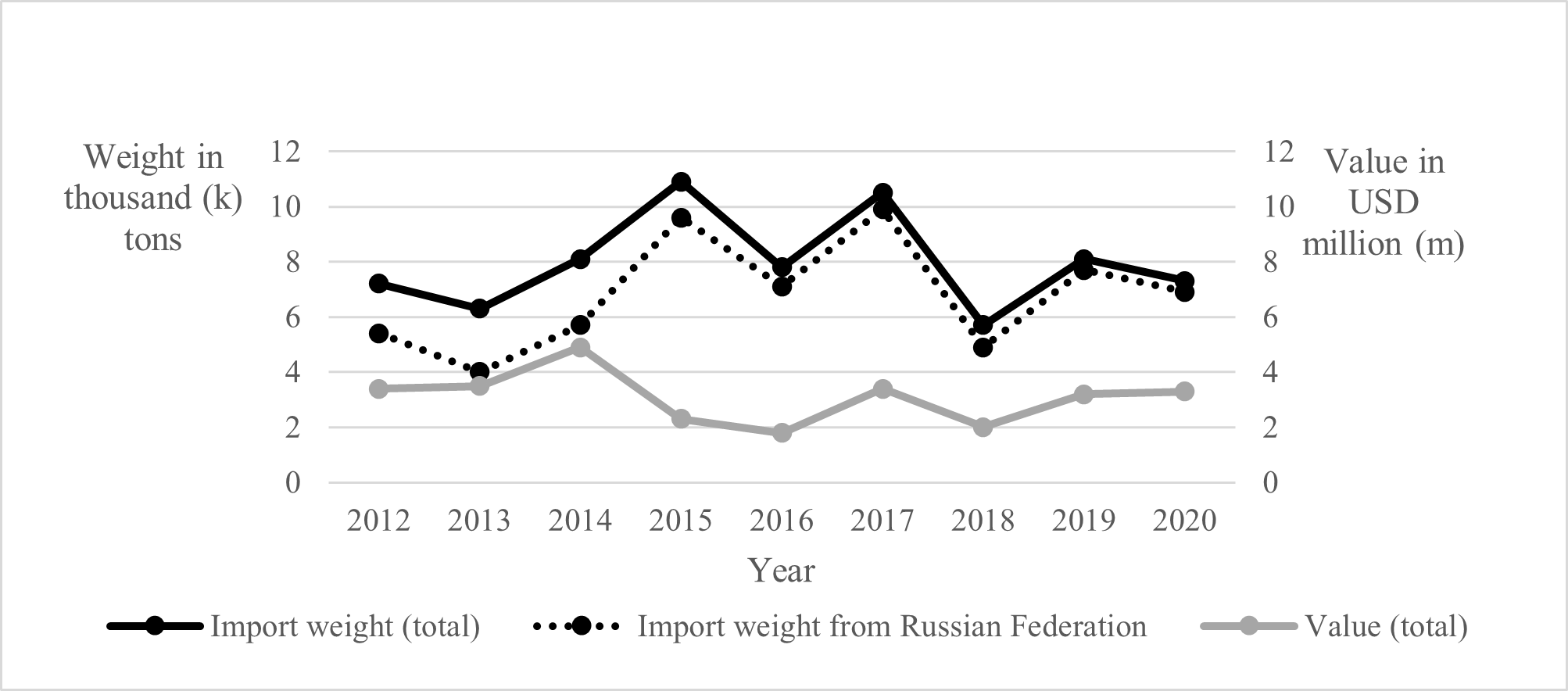

Figure 3. Mongolia’s import of lumber and sawn wood between 2012 to 2020. (data: Chatham House 2024)

According to Chatham House (2024), the import of lumber and sawn wood was at an annual average of USD 3.09 million between 2012 and 2020 (Figure 3), with the Russian Federation as the main trade partner. Tax exemptions are applied for wood imported to Mongolia, what the literature refers to as ‘perverse incentive’ to the potential wood use from internal sources (MMET and REDD+ Mongolia 2018a). The formal reason for applying tax exemptions on imported wood is to conserve local resource (Glauner and Dugarjav 2021, p. 20).

The silvicultural concept in question was based on the 2018 NFI data. This example shows how resistance (rejection of the silvicultural concept) might evolve among domestic decision-makers due to their personal agendas/informal interests (potential link to wood trade) or due to disagreement on priorities (conservation versus the use of local resources). We consider our data too limited to definitely confirm either of these two counter-interests. However, it is important to note that the implementation of policies addressing the sustainability issues of Mongolian forests has been inconsistent for decades (Tsogtbaatar 2004; Ykhanbai 2009; Benneckendorf (2022) in Gradel et al. 2019; Glauner and Dugarjav 2021). The recurrent and persistent failure to follow through on these policies – whether due to counter-interests, lack of capacity, or financial constraints – reflects deeper systemic dysfunction.

Interests and power impacting NFI sustainability

Logically deducted and summarized from the two case studies, the following formal and informal interests of actors in NFI projects are detectable (Table 1). We acknowledge that organisations are heterogeneous and that internal conflicts and disagreements exist. However, we summarize the interests under one actor group based on the observable outcome detected and triangulated through observation of policy implementation, literature and interviews.

As stated on the top of the results section, the formal goals of the actors include mandates, commitment to international conventions, and mechanisms, which represent the overreaching formal interests of the collaborating partners. In this sense, especially the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and the REDD+ mechanism are mentioned in the project literature of both cases. In SDG 17 “partnerships for the goals”, as well as the formal mission of the actors to improve the relationship with other actors is reflected. However, in line with the theory, informal interests were detectable behind the formal interests of all actors (Table 1). These informal interests show a focus on short-term results rather than the long-term sustainability of the NFI.

Donors, who, in the context of NFIs, aim at supporting sustainable development in the Global South, have strategic self-interests in the collaborations. Presence in the recipient country (even when represented by aid agencies) allows them to access first-hand information. Both Tunisia and Mongolia, are located in regions of geopolitical importance. With Tunisia being a MENA country and Mongolia being locked between China and Russia, their locations are linked to issues such as security, migration, trade and resource access.

For donors, working on sustainability issues is increases visibility, which is crucial for the relationship with recipient actors. Further, inputs in the forest sector, which is important in economically weak parts of the countries, serve to camouflage or “greenwash” unsustainable practices of industrialised countries, such as CO2 emissions, mining, trade, controversial refugee policies (especially relevant in the context of North Africa and the EU). To foster their acceptance among citizens and in international fora, donors are oriented on producing project-based success stories. The projects are restricted to four years and donors usually pick three sectors of intervention. In this context, forestry may be a box to be ticked, and their interest may not continue after the four years of project duration. Engaging in an impact assessment of NFI projects may exceed the donors’ interests but is required for reaching sustainability and durability beyond project-based interventions.

Table 1. Formal and informal interests of actors involved in national forest inventory projects.

|

Actor |

Formal interest in NFI projects |

Informal interest in NFI projects |

|

Global North Donor |

Complete mandate (foreign policy and international frameworks and conventions) Resolve sustainability issues Support sustainable development in Global South countries Improve relationship with recipient country

|

Obtain information Produce success stories for improved reputation in recipient and donor country Increase visibility and influence in the recipient country Camouflage unsustainable actions (pollution from industry, mining, trade…) |

|

Global North Aid Agency |

Complete mandate (assist recipient country on behalf of donor and recipient country government) Resolve sustainability issues Improve relationship with recipient country

|

Produce success stories for improved reputation across collaborating partners Improve relationship with the donor as financing partner to secure funding for future projects Access information Career benefit based on successful project portfolio

|

|

State Forest Administrations of Recipient Country |

Complete mandate (manage forests in behalf of the people) Work towards SDG Data transparency Gain knowledge on the status quo of forest Resolve sustainability issues based on science Improve relationship with aid agency and donor |

Maintain revenues Avoid negative consequences resulting from data transparency: conceal sustainability issues, shortcomings in management Decrease workload Personally benefit from the network, education and financial resources of the project Improve position in organisation |

Aid agencies formally aim to provide their expertise to resolve sustainability issues and commit to trustworthy, transparent project management. However, producing success stories, which may take shape as positively biased reports, serves their self-interest to improve reputation across partners, especially the donor organisations on which they rely for current and potential future projects. The project may represent a steppingstone for the career of individuals. The formal, successful closure of a project plus the experience with the donor may contribute to their portfolio. This may be, on the individual level, more important than long-term project outcomes.

Government organisations of the recipient country. Further considerable differences between formal and informal interests were notable for the state forest organisations in recipient countries, including forest services and ministries. While government actors expressed aims to enhance data transparency and to use data for scientific solutions to sustainability issues, these statements were not backed by action.

In Tunisia, the project was closed without launching the planned data dissemination forum. During the NFI project, the ministry’s inaction regarding the public announcement of the NFI advance was noted. Restricting access to NFI data is a tactic to avoid negative consequences as it helps to conceal sustainability issues and shortcomings in management.

In Mongolia, the government pledged to make the wood sector more competitive. However, science-based recommendations and NFI-based silvicultural concepts were disregarded. While the formal narrative is focused on conservation concerns, issues of law enforcement, such as illegal logging and forest fires, prevail and highlight the disconnect between the expressed interests and on-ground realities.

Now that the interests of each actor group were considered, it is important to examine how these interests impact the interactions during the different phases of NFI projects. In the utilized analytical framework, the actor-centred-power (ACP) approach, interests determine how actors use power in form of unverifiable information, incentives and coercion (Krott et al. 2014). In the context of NFI projects, the power elements ‘dominant (non-verifiable) information’ and ‘incentives’ are at play, specifically at the beginning of the projects.

Pre- and early phase of NFI projects: Prior to the launch of projects, aid agencies obtain access to the budget either through the application to open calls or by submitting an NFI project proposal directly to the donor. At this point, aid agencies' knowledge regarding the donor’s formal agenda (or formal interests) and the emphasis on the match of their competencies with this agenda is a crucial type of dominant information. In parallel, recipient government organizations such as ministries and forest services are already involved, displaying interest and a proactive attitude towards the NFI project. This displayed interest and commitment may be classified as dominant information as well. An important driver to project acceptance is the financial incentive applied by the donor, as attractive positions and learning opportunities as well as potential follow-up projects may come along with NFI projects.

Implementation phase: In the intermediate or implementation phase, the impact of the power elements, incentives and dominant information, decreases. This may slow down or hinder either the NFI project itself or follow up policies created based on NFI data.

Firstly, the power of incentives applied by aid agencies loses its effectiveness as roles are assigned and the course of the project is set. Actors and individuals who sought to benefit from the project but were not afforded the opportunity may choose to withdraw. In case the course of the project triggers a mismatch with interests, for example disagreement on payments for materials, what data and how data is collected, how it is used or distributed; domestic actors even demonstrate resistance and boycott.

In the same vein, dominant information regarding interest and commitment to NFI projects loses its effectiveness in the constellation of actors, especially when promises are not kept and responsibilities are not taken on.

Closing phase: Once an NFI project is completed, the aid agency hands over the NFI report to the recipient country government and the final project report to the donor. With the formal procedure of receiving the deliverables, the donor’s mission concludes. The recipient country being the owner of the forest data, holds the authority to determine its use, including decisions regarding dissemination to national and international fora. Meanwhile, consultants and aid agency staff move on to other projects or countries.

But what happens to the national capacity for forest monitoring, which potentially improved thanks to trainings received in the frame of NFI projects? Highly skilled employees may seek to advance their careers and shift to more attractive jobs than government positions, which often lack inner-institutional incentives and opportunities to grow (interview 30, 36). This aspect itself reflects interests (to keep skilled employees) and power (ability to apply incentives which render the position attractive).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

NFI-related interests of the Global North actors

We observed that the NFI projects of both countries, Tunisia and Mongolia, prioritised the agendas of the foreign donors, the World Bank in Tunisia and the German ministry BMZ in Mongolia, respectively. One key point on their agendas is the promotion of the REDD+ mechanism in developing countries (World Bank 2009, BMZ 2015). This is because the support of the REDD+ mechanism is embedded in industrialised countries’ foreign policy, linked to their commitments to international development frameworks (Karsenty and Ongolo 2012; Allan and Dauvergne 2013). Consequently, promoting REDD+ positively impacts their reputation and position of negotiation internationally on climate change causes and adaptation.

Both NFI projects were planned and implemented under the assistance of aid agencies, FAO in Tunisia and the GIZ in Mongolia. In the official project documentation, we noted an absence of information regarding each country’s political context, notably, risk factors such as political instability or systemic corruption were not mentioned although academic literature and news reporting are available (example: Reeves 2014; Capasso 2021). Conflicts linked to the project as we detected in the Tunisian case study, and counter interests of decision-makers, as we found in the Mongolian case, are as well rarely represented in the official documentation.

Risk factors, such as 1- political instability, 2- systemic corruption, 3- conflicts, 4- counter-interests, can negatively impact the implementation of policies and projects. It is likely that these points are not openly addressed because of two reasons. Firstly, both actor groups of the Global North, foreign donors and aid agencies, have an interest in producing success stories in order to improve their own position. Under the actor-centred-power (ACP) framework, such positively biased information utilized by actors can be classified as the power element “dominant information”.

For the specific context of the two studied NFI projects in Mongolia and Tunisia, our empirical data hence supports the first hypothesis.

H1: Actors of the Global North formulate and implement forest inventory projects in the Global South based on their informal and formal interests.

This aligns with (Forebs and Russo 2011, p. 99) who observed that in Guatemala, NFI survey methodology, analysis, and presentation were driven by FAO and “global interests” such as reporting to the FAO Forest Resource Assessment (FRA), instead of local needs.

Empirical evidence from the two cases shows that immaterial and material incentives fostered the project's acceptance among domestic actors, for example, the opportunity to participate in training and consultancy, accompanied by the provision of a foreign budget for planning and implementing the NFIs.

The incentives matched formal interests of domestic ministries and administration to produce scientific information regarding forests. Simultaneously, the financial incentive addressed informal interests in the “chronically underfunded” forest administrations.

From the perspective of the staff of domestic state and non-state organisations, participating in NFI projects comes along with important opportunities for bureaucrats inside the organisation: 1- receiving training beneficial for their careers, 2- strengthening their position in the organisation, 3- to benefit financially, for example by securing a role as a consultant in the project or by participating in financially supported trainings and workshops, 4- networking and travel opportunities. This last point shows that, despite our data’s support of H1, that NFI projects were driven by the interest of foreign donors, inventory projects can be in line with the interests of the participating domestic actors and individuals, as long as they are beneficial.

NFI-related interests of domestic actors

The aid agencies that were entrusted with planning and implementation of the projects, took on roles that exceeded assistance: Our data indicates that in Mongolia, the aid agency gave a crucial impulse for the NFI project. In Tunisia, policies impacted by foreign donors paved the way for the inventory project, and the agency navigated the project during periods in which the national partner was weakened due to political instability or when the partner adopted a passive role due to internal and external conflicts. This sheds an interesting light on the ownership aspect of NFI projects.

During project implementation, the interests of domestic actors were not fully taken into account (compare to the section on How in-country dynamics impact NFI projects). For this reason, we observed different types of resistance among the domestic partners in both cases, either during the NFI implementation (Tunisian case) or afterwards when the aid agency developed new projects based on the NFI data (Mongolian case).

Unconsidered key-interests of domestic state-actors as 1- participation in decisions regarding leadership of projects and veto-right, 2- compensation of the staff (staff was not always encouraged by the incentive system of the domestic organisation), 3- counter-interests in regard to transparency and use of NFI data resulted in resistance, passiveness and withdrawal.

This shows that the empirical data collected from the case studies in Tunisia and Mongolia support the second hypothesis.

H2: Lack of consideration of domestic actors’ key interests leads to the withdrawal of domestic actors from NFIs and follow-up projects formulated and implemented by the Global North actors.

NFIs and forest monitoring, in general, are complex science-based programs that deliver forest data, which is necessary for informed decisions in policy processes that address sustainability issues such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Krott and Zavodja (2023) emphasise that taking up such scientific solutions in practice must be beneficial to decision-makers. In line with this statement, Nago (2021) highlights that, in the Global South, a lack of addressing local needs paired with a strong international actor may produce irrelevant policy outcomes. The same study shows that aid agencies are not only providers of assistance but also foster their own interests.

In the context of forest monitoring, the neglect of domestic actors’ interests creates important obstacles to the repetition of NFI. In addition, governments informal or “vested” interests, as Janz and Persson (2002) name it, can be contrary to international organisations’ aim to make forest data transparent and accessible to the public. The detected resistance or passiveness of state actors during NFI implementation phases and follow-up projects corresponds well to the infringement tactics described by Ongolo and Krott (2023), especially tardiness and boycott, which are employed by dominated actors, to defend their interests in an unequal power relationship.

Based on our findings and the arguments of the cited authors, we suggest to higher prioritise the aforementioned informal interests of domestic actors and seeing them as part of local needs and determining factors for the sustainability of NFIs. Here, it is crucial not to exclusively focus on government actors, but to include non-state actors from early stages on, as we will further explain in the following section.

Importance of domestic non-state actors for ‘Country Ownership’ of NFIs